Art Nouveau in Bratislava

Art Nouveau architecture in today’s Bratislava is an example of the fruitful coexistence of different influences and concepts from a number of architectural designers. The Hungarian national style, the Viennese Secession of Otto Wagner and the Arts and Crafts movement from England all played roles in the city’s early 20th century architecture.

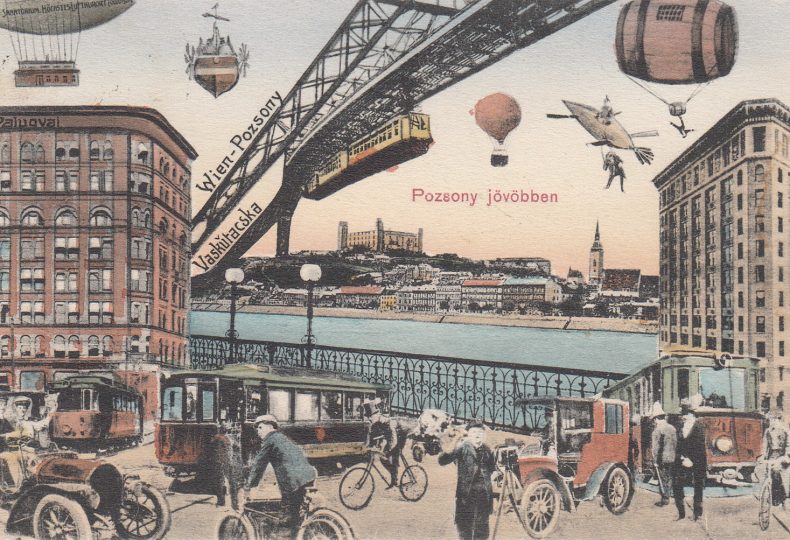

Incredible dynamism in discussions about urban planning and construction marked the period between 1890 and the outbreak of World War I. Just in those years alone came a framework for the city that would last into the 21st century. It comprised the first ever regulation of construction and expansion of Pressburg, and later Bratislava, which served as the foundation for forming the inner city ring, urban boulevards and new residential districts, as well as the development of public transport and industry. In that same time, the city’s appearance was also undergoing a transformation wrought from changes in how architecture was viewed. The new trends brought about by Art Nouveau were particularly evident in the neighborhoods of the city the new regulations now covered. A rising concentration of this recently developed architecture was evident along the perimeter of the inner city ring, in the section near the Danube River and on the slopes of the Little Carpathian Mountains, where in those years development seemed to stop.

The Hungarian government’s investment into education, visible in the construction of schools, was having a significant impact on the city’s appearance. In the first years of the 20th century, almost a dozen new educational institutions were built in Pressburg. These included the unconventional Király Főgimnázium (Royal Secondary School) and the Church of St. Elizabeth, standing out in the Danube Quarter and designed by Ödön Lechner, the top architect of the Hungarian Secession and National Style.

Other leading Hungarian architects active in fin-de-siècle Pressburg were Gyula Pártos and Zsigmond Herczegh. Under Budapest’s strong influence, lesser-known architects and builders such as Jenő Schiller and Gyula Schmidt were engaged in a number of similar-vein projects.

An echo of Wagner’s own conception of Art Nouveau is the former Korpskommando, designed by Viennese architect Josef Rittner. Otto Wagner’s architectural work also inspired Albert Kálmán Körössy and Géza Kiss’s design of the Hungarian Foreign Exchange Bank on the main square.

Meanwhile, a completely different trend was arriving via Vienna to Pressburg in a project by architect Ludwig Baumann. He had been commissioned by Antal Durvay to design a series of residential units in the Danube Quarter that featured front gardens. How these blocks were constructed, the suggestion of vernacular architecture and the naming of them as “cottages” was a direct response to the garden cities found in England and the “Arts and Crafts” movement from there.

Seen in the early 20th century as major urban streets and squares, present-day Štefánikova, Palisády, Štúrova, Šafárikovo námestie and Jakubovo námestie were showcasing the different trends in Secession architecture. The richly decorated façades of the houses there conformed to this concept. Today, they still document the taste and aesthetic preferences of the former owners and the artistic views of the architects that designed them. Yet they also reveal something about the relationship that existed between Pressburg’s elite and architecture.

This digital platform seeks to call attention to the wealth and diversity of the architectural legacy of the early 20th century, when Bratislava’s modern identity started to be born.

HM